Extraction/Abstraction: human power over the climate

In these images there is a beauty that wounds. They document forty years of human impact on the planet. With an unbiased, often top-down view, Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky explains better than any scientist the cost of supporting eight billion people on an earth that is not limitless and to which no one has ever asked permission

The impact of a diamond mine in Kimberley, South Africa

The impact of illegal oil bunkering on the Niger River in Nigeria in 2018.

From above, the world is a little more frightening, because our eyes cannot hide in ignorance and dive into the beautiful and the ugly with - out warning or filter. Think of Sicily, whose slow but inexorable process of desertification is invisible to “earthlings” unaccustomed to living in contact with nature, but violently up - sets the gaze of those observing the island from an airplane window.

It is no coincidence that the view from above is one of the favourite perspectives of Edward Burtynsky, Canadian born in 1955, a legend of nature photography who has been travelling the planet for forty years, driven by a mission: to capture the anthropic impact on green and uncontaminated landscapes, now dominated by man, who has never liked to ask for permission.

These images and the previous one: images from Burtynsky’s photographic work on Xilella fastidiosa, which is destroying olive growing in Apulia.

The shots come from all corners of the globe - from the potassium mine in Berezniki (Russia) to the salt flats of Cadiz (Spain), via nickel processing plants in Sudbury (Canada) or a waste pond near a diamond mine in Wesselton (South Africa) - but Burtynsky has a special wish for the exhibition, and calls for a comprehensive view: “I ask the viewer to dismiss preconceived notions of where beauty can be found and to travel with me, for example, to the landfills of Nairobi to face the reality and the consequences of a planetary culture based on plastic use. These images show the human condition, without approval or condemnation: they are simply the reality of our times and illustrate the huge cost of feeding eight billion people on a planet that is not infinite”, writes the photographer in a text in the volume “Burtynsky Extraction / Abstraction” (Steidl, Göttingen, 2024), translated by Barbara Del Mercato.

Mines, quarries, refineries, factories and waterways disfigured by industry are part of the (sometimes shocking and gloomy) landscape proposed by Burtynsky, who is also known for his documentaries shown at festivals all over the world.

Within the walls of M9, the multimedia museum of the 20th century in Mestre (11, Giovanni Pascoli St.), it will be possible to experience the largest anthological exhibition dedicated to the career of the artist from St. Catharines until 12 January 2025. ‘BURTYNSKY: Extraction/Abstraction’, the title of the exhibition curated by Marc Mayer (former director of the National Gallery of Canada and the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Montreal), is divided into six thematic sections that are not limited to large-format pictures: the viewer will be able to see, for example, the drones that allowed Burtynsky to self-reinvent during a crucial phase of his professional life.

The Berezniki potassium mine, the salt flats of Cadiz, the nickel processing plants in Canada: the world is bleeding

Cathedral Grove, forest in British Columbia (Canada), set of Star Wars and now a destination for pilgrimage overtourism.

In fact, we are talking about an exhibition that acts more like an in-depth textbook, with the aim of investigating the facets of the most pervasive emergency of our historical period: climate change. Burtynsky has also chosen to focus on the issue of agriculture and, as far as Italy is concerned, on the effects of Xylella fastidiosa on Apulian olive trees. Increasingly high temperatures favour the proliferation of a bacterium that, according to the latest monitoring by Coldiretti, has infected more than twenty-one million plants in Apulia, causing damage worth billions of euros.

The salt flats of Cadiz, Spain, shot from above in 2013. This area, at the centre of a protection programme since 2021, has seen some of its biodiversity lost in 70 years.

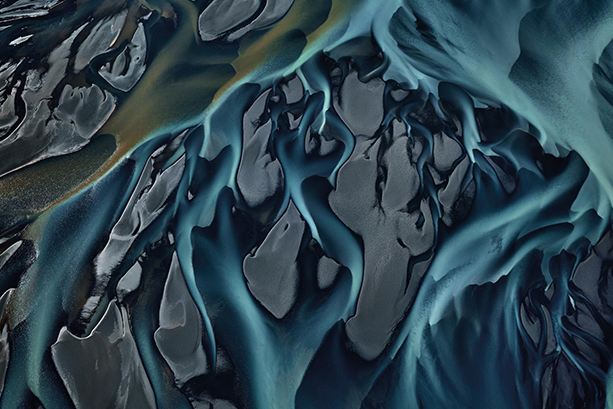

The glacial Thjorsa river in Iceland in 2012, when a construction plan for dams, geothermal power plants, aluminium smelters and an oil refinery was advancing.

Photography can also be a vehicle for bringing together, and making more accessible, climate and financial issues that can no longer be dealt with separately: the economic damage of this crisis, according to a study published in Nature in April 2024, is already six times greater than the cost of meeting the Paris Agreement’s target (not to exceed +2°C increase in the global average temperature compared to pre-industrial levels, and preferably to limit it to +1.5°C). In this context, according to Burtynsky, art can still emerge as a source of hope and awareness, because it can suggest “a more fulfilling way of being in the world, with a deeper meaning”, also showing us “another way forward” and embracing “the best that science has to offer”. A concept that is steadily reinforced in the documentary ‘In the Wake of Progress’ (2022), co-produced by Burtynsky and presented in an immersive mode and exclusively in Italy as the final act of the exhibition.

The Berezniki Potassium Mine, Russia, photographed in 2017.

Nickel mining slag turns waterways into orange in Sudbury, Ontario (Canada, 1996).

Fabrizio Fasanella

Journalist at Linkiesta, he is an environmental expert and editor of the Greenkiesta newsletter.